Q&A with Jacqueline

Jacqueline talks about her lifelong interest in WWI and how a 1911 book for women—and her family's wartime experiences—inspired the novel.

You are widely known as the author of the New York Times bestselling Maisie Dobbs books, a beloved series of mysteries set during and in the aftermath of the Great War. Your new novel—The Care and Management of Lies—while a standalone book and a departure from Maisie Dobbs, is also set in England during the Great War and tells the story of the lives of people deeply affected by the conflict. Of course, this summer will mark the centenary of the Great War. What draws you to this time?

I have long been drawn to the period—the Great War—WWI—and its aftermath, inspired by a curiosity that began in early childhood, when I was deeply aware of the lingering pain of "war wounds" suffered by my grandfather, who had seen action during several of the war's most notorious battles. I was aware of the effect those wounds and his lingering shell-shock had on my family, and though it was at first a childish curiosity, it grew into a deep adult interest by the time I reached my teens, when I was also studying the war poets in school and becoming very emotionally affected by the work. My interest brought me back to the same question—what does war do to ordinary people swept up in its chaos? The history of any war is drawn on a massive landscape, but I'm interested in zooming the camera in, then asking what might have happened to a person in this or that situation. My grandfather was still removing shrapnel from his legs when he died some fifty years after the Battle of the Somme (1916), and my grandmother was partially blinded during an explosion at a munitions factory where she was working with volatile explosives in 1915—those examples underscore a comment from one of the characters in my novel, Birds of a Feather: "That's the trouble with war, it lives on inside the living."

The Care and Management of Lies tells the story of girlhood friends Kezia Marchant and Thea Brissenden as they navigate the tumultuous time in which they are living. Thea has become a passionate suffragette and Kezia, engaged to marry Thea's brother Tom, is headed for a traditional married life of domesticity—until war breaks out. The novel paints a moving picture of a friendship strained by a world in turmoil and the shifting notions of the roles of women. Are there ways in which the questions the novel raises echo in our own time?

There are several aspects of the book that mirror our times. The passage of time can test any friendship—change of job, moving house, choice of life-partner, and then children come along, and life separates people who have once been inseparable. The transition from girlhood into womanhood, and the opportunities and changes that come as part and parcel of that move—leaving school, going out to work, moving house, or choosing to live another life—have made for a crucial time in the lives of women throughout the past century. This test of change is what has happened to Kezia and Thea. Although quite different, they have been friends since girlhood and have truly admired each other's strengths—then the choices that each has made separate them, and they move apart. Passionate Thea becomes involved in the fight for women's suffrage, which was far more heated and violent in the UK than here in the US. Her beliefs put her at odds with Kezia at the onset of war—and Kezia, as one who is about to be married and wants nothing to stand in the way of her envisioned happiness, would like to think that the threat of war is going to go away. But it doesn't, and life is again changed for both of them—yet in that unexpected transition, it seems they gain a new sense of mutual respect, and each draws upon strengths the other holds dear. Kezia surprises Thea with her backbone when she effectively steps into her husband's shoes when he goes to war, while Kezia admires Thea's choices despite the fact that she fears for her friend's wellbeing. I think many women can identify with the fact that cherished friendships can be threatened by the life choices each woman might make—and this was a time when choices and new paths never before available to women became part of the equation.

You have said that The Care and Management of Lies first began to form in your mind twenty years before you wrote your first novel. What inspired this story and why did you wait to tell it?

When I was in my mid-twenties, I had great fun working weekends with a friend at her stall in London's Portobello Road Market. We dealt mainly in art deco pottery, jewelry and other odds and ends. But you have to keep a stall stocked, so I often went to jumble sales (rummage sales here in America) to find pieces I could resell. It was while sorting through a pile of other people's unwanted "stuff" that I found a very battered copy of The Woman's Book (Edited by Florence B. Jack, published 1911). The spine was cracked, the pages were foxed, and the cover was completely battered and falling off. But it was the inscription that captured my attention and imagination, for the book had been given to a young woman on the occasion of her marriage in the summer of 1914. It took my breath away. I wondered if her young husband had gone to war, whether her fledgling marriage had been ended by the conflict—had she been widowed? Did he come home? Was he wounded? How did they keep their love alive in wartime, and what did life look like for this bride after the war? The book cost me five pence. Over the years a story seeded itself in my mind, though sadly the book left my hands (I gave it to a friend who thought she could have it re-bound, but of course as these things happen, she married and had children, then moved, and I emigrated). It was after I became a published author that I knew I wanted to write my story one day, and I managed to acquire another copy of The Woman's Book—in fact, I have acquired a few! In my story the book is given as a gift to Kezia Brissenden on the occasion of her marriage, by her best friend and sister-in-law to be, Thea—but it is given as a bit of a dig, a comment on the bride's life to come.

I took so long to tell the story because it was more than a few years before I became a published author, and then I was deep into writing about another strong woman character, Maisie Dobbs. But the time came when I just knew I had to write the book that had been with me for so long, and fortunately, my publisher was incredibly supportive of my dream—because to write this story has been something of a dream come true. I've found it quite hard to leave the work behind, because I became so engaged with these characters.

Most chapters of the novel begin with a quote from The Woman's Book. At a time when women were fighting for the right to vote, this book seems to have all the hallmarks of a tome meant for the housewife to be and yet you describe it as being so much more, as demonstrating the very best of womanhood in all domains of endeavor. Do you see its relevance today? Or ... does anything compare to it today?

The Woman's Book was a very popular book in its day, so quite a few were published. The amazing thing about the book is that, although at first blush it looks like yet another tome on household management—and certainly Kezia has assumed that, because she hardly uses it—deeper reading reveals it to be very much for the modern woman. Though you can read sections which advise you on topics such as where to seat the Prime Minister if the King is present for supper, there are other sections on women in the workplace, women in politics, how to be a political canvasser. Another section covers women in agriculture, and though you can learn how to black a stove, or get stains out of your whites, you will also find out how to make money from freelance writing. I liked that section!

Frankly, I have never seen anything similar today—probably the last book that mirrored The Woman's Book was Superwoman by Shirley Conran, published in 1976.

It bears adding that there are also quotes from military handbooks issued in 1914 to officers and men sent to fight for Britain and the Empire—what these books have in common with The Woman's Book is a deep sense of order, as if everything has its place, and must be in that place, or chaos will reign. And that mirrors one of the key elements of the time I find so very interesting—that at the outset of war in 1914 there was a cherished Edwardian veneer of order, yet with the war came such disorder. From the rise of the middle class to the development of opportunities for women (the vote was a result of women's involvement in the war), right up to enormous changes in world geopolitics and alliances—1914 really was the true start of a bold new century.

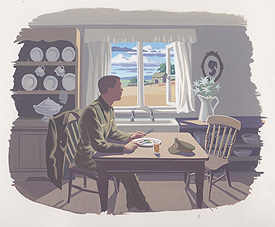

Food plays out deliciously as a core theme throughout your novel. In her letters to Tom, Kezia describes the mouth-watering meals she might cook for him, and even Tom's fellow comrades in the trenches find comfort in the meals Kezia imagines on the page. You write: "Tom Brissenden was eating the same food as any other man in the encampment. But with these letters, he was tasting love..." It is said that soldiers at the front—then and today—often write about the food they miss from home. What is the relationship between food and nostalgia in The Care and Management of Lies?

When people are away from home for an extended period of time, away from the comforts of home and those they love, food becomes something of a lightning rod. I know just from being on a book tour, for example, that towards the end of my travels I am aching to come home to I can sit down in my kitchen and have a cup of tea with my home made oatmeal for breakfast!

A war zone is invariably a desolate, unforgiving place, and food—thoughts of home-cooked food especially, or a favorite dish—takes on a new level of significance. With food comes a sense of being cared for, a sense of being nourished and above all, loved. Army rations have changed dramatically over the years, but the same equation still holds true—the military is primarily interested in calories in and calories out. Men and women in combat situations use an extraordinary amount of energy, and military cooks have the task of meeting the calorific needs of a fighting force. Today's army cooks have more ways of producing and transporting large quantities of food, but there is probably not a deployed serviceman or woman who does not dream of that first meal back at home. The son of my oldest, dearest friend returned last year from his third tour of duty in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. On one occasion during his deployment I was visiting their home, and he phoned to speak to his parents at dinner time. The phone was put on the table, on speaker, so we could all talk to him, and he wanted us to tell him all about what we were eating—one of his favorite dishes, as it happened, cooked by his mum. I talked about it later to my friend, and she said that for both her husband—an army officer—and son, food became the most important thing for them when deployed, and receiving a special food item from home—perhaps a cake or some cookies—was tantamount to being given something very precious. When he called it was always at dinner-time, and he always wanted to know exactly what was on the table, in great detail.

Nostalgia is fed by the emotions that come with separation—and in wartime that separation becomes more acute, encompassing the sense of loss of home, family, loved ones, warmth, comfort, freedom from fear, along with so many other emotions. How the men were fed in WWI became a crucial component in the issue of morale.

As Tom enlists to fight for his country and heads off to battle, he and Kezia are forced to learn to love in a time of war. We have watched the moving images of soldiers these last many years in this country and elsewhere separate routinely from their loved ones to serve a tour of duty. What differentiates love in a time of war from love in a time of peace? How does war affect marriage, and how do we see this played out in Tom and Kezia's marriage?

I think love becomes more urgent in a time of war. One only has to read stories about the number of couples who were wed at the outset of the Great War, the Second World War and subsequent conflicts. Men and women are changed by war—and a military spouse is as affected as the serviceman/woman. Keeping relationships immediate and remaining connected is much easier with today's technology, whereas in the past the spouse at home had to depend upon letters and cards, and of course for the soldier, those packages from home held enormous importance, for they often contained food items. The British army had a very efficient postal service in WWI—probably more efficient than the post today—with letters often taking only two days to arrive from the front to a house in England. In Tom and Kezia's marriage, we see how they keep their relationship immediate with letters—but those letters are written as if they were together, rather than apart. This keeps their love very much alive, in the present.